Practical Usage of Pairwise Testing

Using pairwise test design technique to represent components in Storybook.

DALL-E 3 prompt: you are a software engineer. You have a set of data, battery levels: 0%, 19%, 20%, and 100%, isWireles, isConnected, and isCharging. Based on this data, render various UI components of the battery

Recently, I’ve been mentoring a junior test engineer who asked me a question: «How do we apply pairwise testing?» I was confused because, from my point of view, it is so obvious that it does not need any explanations. But if the question was raised, it demands an answer.

According to the definition of pairwise testing (or all-pairs testing), it is a type of combinatorial testing (2-way testing in combinatorial terminology) that, for each pair of input parameters to a system, tests all possible discrete combinations of those parameters.

But it does not clarify noobie questions: How do you choose pairs? How do you identify the proper set of input parameters? In which cases you should use this technique? All these questions can be answered only after a complex theoretical study.

Thus, for a brief response, I turned to a real-life example where we use pairwise testing in a current product. And there are such cases in Storybook’s components!

Unfortunately, a little introduction to pairwise testing still be required:

Pairwise testing reduces test cases by examining all unique pairs of input variables rather than exhaustively testing every possible combination. This technique cuts down on testing time, resources, and the overall number of test cases required.

If your aim is 100% test coverage (cover of all possible combinations) of a system of n-parameters with k-combinations, and if the number of combinations for each parameter is fixed (which is quite rare for real-life production systems), then, according to the multiplication principle of counting, you will have to perform k^n tests. (For accurate combinatorial calculations, a binomial coefficient is used.)

A seemingly small system of six parameters with four values each requires the execution of 6^4 = 1296 tests for 100% coverage. Adding just one more parameter dramatically increases the number of tests: (6+1)^4 = 2401. A real-life production system with hundreds of parameters and dozens of values will demand tens of millions of tests for 100% coverage [1] — that is what it means: that exhaustive testing of all possible combinations is not always feasible [2].

Here comes all-pairs testing, which allows maximizing input coverage while minimizing the test suite size. Unhappily, with some limitations:

- You will not get 100% coverage [1] (although, in practice, you don’t need it);

- This approach is not effective for testing event sequences [1] (e.g., software with time-dependent logic) — this leads to absurdly many combinations;

- A large number of parameters made it time-consuming and effort-consuming. Again, this led to too many combinations, the execution of which would not allow you to provide any budget for testing.

Despite the flaws above, this technique is excellently applied to a system with a limited number of parameters and values. In this case, we can achieve a pretty decent test coverage with determined parameters rather than using random ones [3].

This system can be a Storybook, a development environment tool that is used as a playground for UI components. It allows the creation and testing of UI components in isolation. Each UI component (if it is not a composite one and is made just enough) usually gets a limited number of parameters (Props) for rendering ⇒ you can predefine Props using a pairwise test design technique.

A real-life example:

Our project has a component of the battery of the IoT device. The battery, in addition to the percentage of charge, can represent several other parameters: type (wireless or not), connection (connected to the charger or not), and charging status (charging or not, depending on the connection).

The next step after choosing the system under test (in our case, it is a battery component) is determining the possible parameters’ values:

- For battery level were chosen boundary values of UI’s states —

batteryLevel: 0,19,20, and100(the «expert judgment» choice of values is justified and is a common practice [4]); - Battery type —

isWireless: boolean; - Connection status —

isConnected: boolean; - Charging status —

isCharging: boolean; - In case both parameters

isConnectedandisChargingaretrue, UI should show a charging sign; if both arefalse— no sign; in other cases — an error sign.

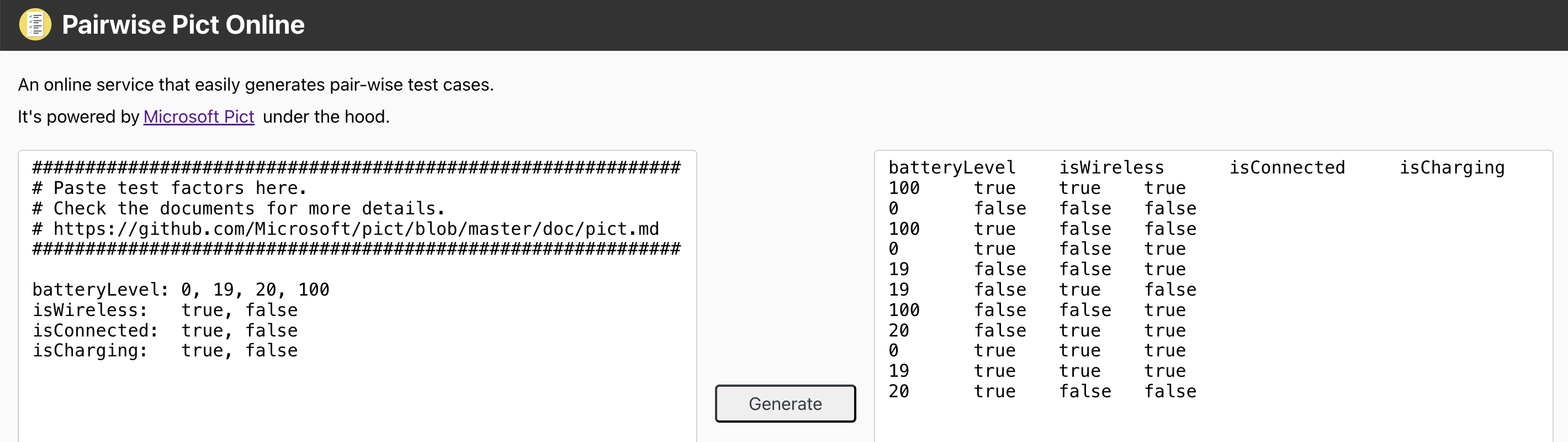

Then, determined parameters and values are passed to a pairwise test case generator. There are a lot of available tools, including web-based ones, such as Pairwise Online Tool and Pairwise Pict Online powered by Microsoft Pict. I chose the last one to generate test cases because of its severe mathematical base.

Fig. 1. Pairwise test cases (generated in Pairwise Pict Online)

Onwards, test cases’ values are passed to the component in the story (battery.stories.tsx) for rendering.

import type { Meta, StoryObj } from '@storybook/react';

import { Battery } from './battery';

const meta: Meta<typeof Battery> = {

component: Battery

};

export default meta;

type Story = StoryObj<typeof Battery>;

export const Primary: Story = {

render: function Render() {

return (

<>

<Battery

batteryCharge={100}

isWareless={true}

isConnected={true}

isCharging={true}

/>

<Battery

batteryCharge={0}

isWareless={false}

isConnected={false}

isCharging={false}

/>

{/* And so on… */}

<Battery

batteryCharge={20}

isWareless={true}

isConnected={false}

isCharging={false}

/>

</>

);

},

};

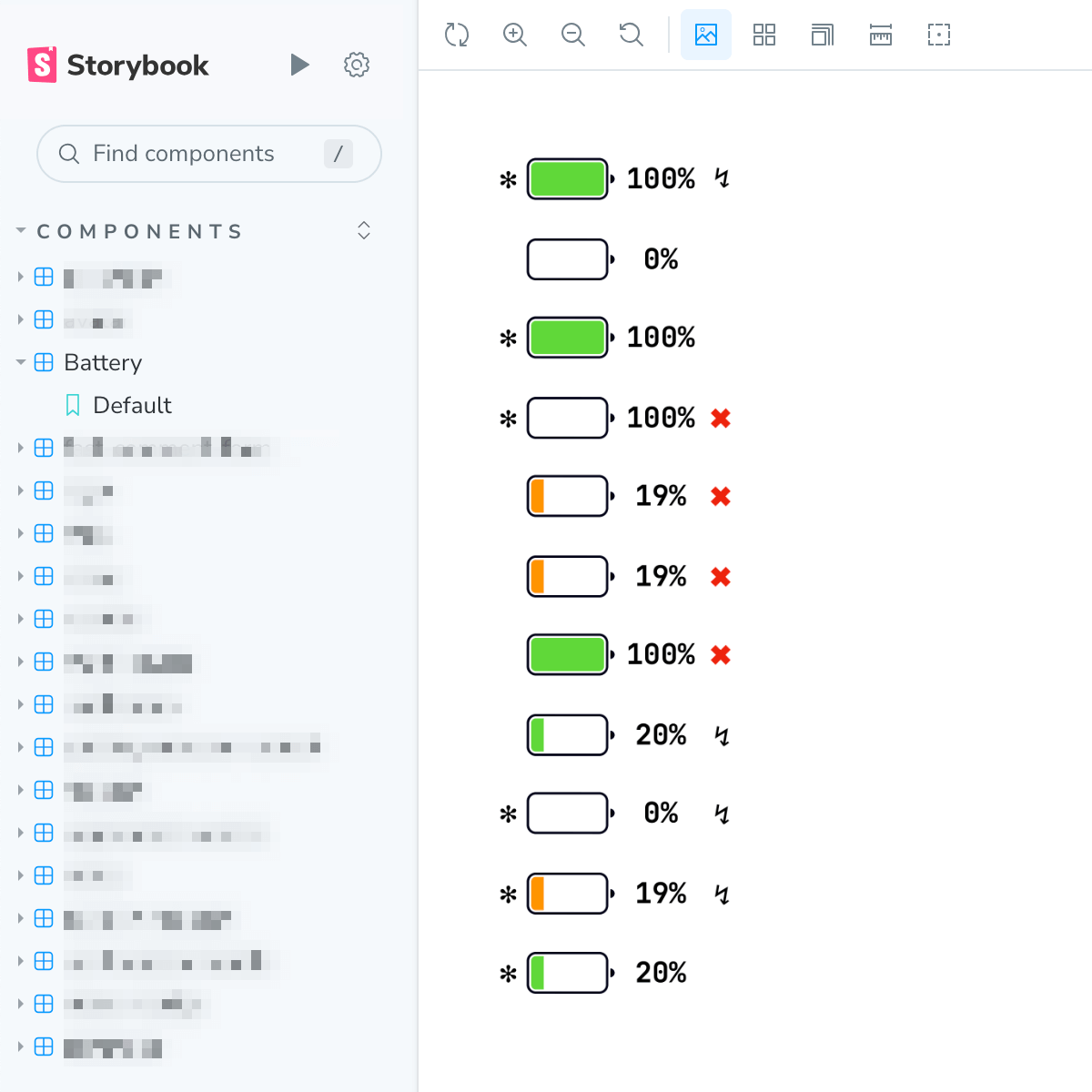

Now, after building a Storybook app, we can observe a battery component in different variants, conditioned by precalculated values.

Fig. 2. Pairwise test cases in Storybook’s story

Surprisingly, after specifying these values to represent a battery component, a bug was discovered in the component’s logic. So, the technique works!

For further development of the technique and enhancing test coverage, you can switch to full-scale combinatorial testing — instead of 2-way interactions (pair-wise), start using a tree- of four-way interactions with the IPOG algorithm [5]. But keep in mind this will significantly increase the number of combinations.

The Storybook itself is an excellent tool for testing UIs, but it is beyond the scope of this article.

Read more:

- Pairwise Testing: A Best Practice That Isn’t by James Bach and Patrick J. Schroeder;

- Introduction to Combinatorial Testing — presentation by Rick Kuhn, National Institute of Standards and Technology, Carnegie-Mellon University, 7 June 2011;

- List of papers on combinatorial testing, National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST);

- Pairwise Testing;

- Pairwise Testing Explained with Tools & Examples;

- Pairwise Testing | What It Is, When & How to Perform?

- Pairwise Testing in the Real World: Practical Extensions to Test-Case Scenarios.

References:

- D. Richard Kuhn, Dolores R. Wallace, Albert M. Gallo Jr., “Software Fault Interactions and Implications for Software Testing,” IEEE Transactions on Software Engineering, Volume: 30, Issue: 6, pp. 418–421, June 2004, DOI: 10.1109/TSE.2004.24.

- Renée C. Bryce, Yu Lei, D. Richard Kuhn, Raghu Kacker, “Combinatorial Testing,” Ch. 14 in Handbook of Research on Software Engineering and Productivity Technologies: Implications of Globalization, edited by M. Ramachandran and R. Atem de Carvalho, IGI Global, 2010, pp. 196–208. DOI: 10.4018/978-1-60566-731-7.ch014.

- D. Richard Kuhn, R.N. Kacker, Yu Lei, “Random vs. combinatorial methods for discrete event simulation of a grid computer network,” Proceedings of Modeling and Simulation, World, 2009, pp. 83–88.

- Raghu N. Kacker, D. Richard Kuhn, Yu Lei, James F. Lawrence, “Combinatorial testing for software: An adaptation of design of experiments,” Measurement, Volume 46, Issue 9, November 2013, Pages 3745-3752.

- Yu Lei, Raghu Kacker, D. Richard Kuhn, Vadim Okun, James Lawrence, “IPOG: A General Strategy for T-Way Software Testing,” 14th Annual IEEE International Conference and Workshop on Engineering of Computer Based Systems (ECBS 2007), 10 April 2007, DOI: 10.1109/ECBS.2007.47.

Copy @ Medium