One More Technique to Avoid Timeouts as Fix of Flaky Tests

Sometimes, as a test engineer, you have to find better solutions to previous fixes if they are insufficient.

A while ago, I wrote a controversial article about fixing flaky tests by adding timeouts in tests, of course, with a disclaimer that it’s only suitable in exceptional cases.

One of the cases (№2) was that a <canvas> element in the test was unavailable for interaction, while the Playwright considered the element actionable.

The fix was to add timeouts before interaction with a <canvas> element because there was no way to determine its readiness.

Unfortunately, this «fix» still allowed the test to fail — the fix made the test more «stable» but not 100% enough. According to my brief statistics, it could be one time of the false positive failure of that test in 1–2 weeks. That is nearly 0,5–1% failure rate based on around 100 weekly test runs.

Both the fix and that it did not completely solve the issue are common problems for flaky tests studies:

- Increasing delays between actions that involve fetching or loading [1] or stalling some part of the code for a pre-specified time delay using

sleep[2] are among the popular solutions for fixing flakiness. - While this does not fix the root cause directly [1], this decreases the chance of a flaky failure [2].

- Even in Microsoft, some flaky tests are found to be flaky more than once because the developers’ initial fix for the flakiness was inadequate [3].

For a proper fix, you have to examine the application from the top (inspecting HTML and JS) to the bottom (network level) and find indirect ways to perform a check. One example of such an indirect check is waiting for a particular state of the related element before clicking on the desired one.

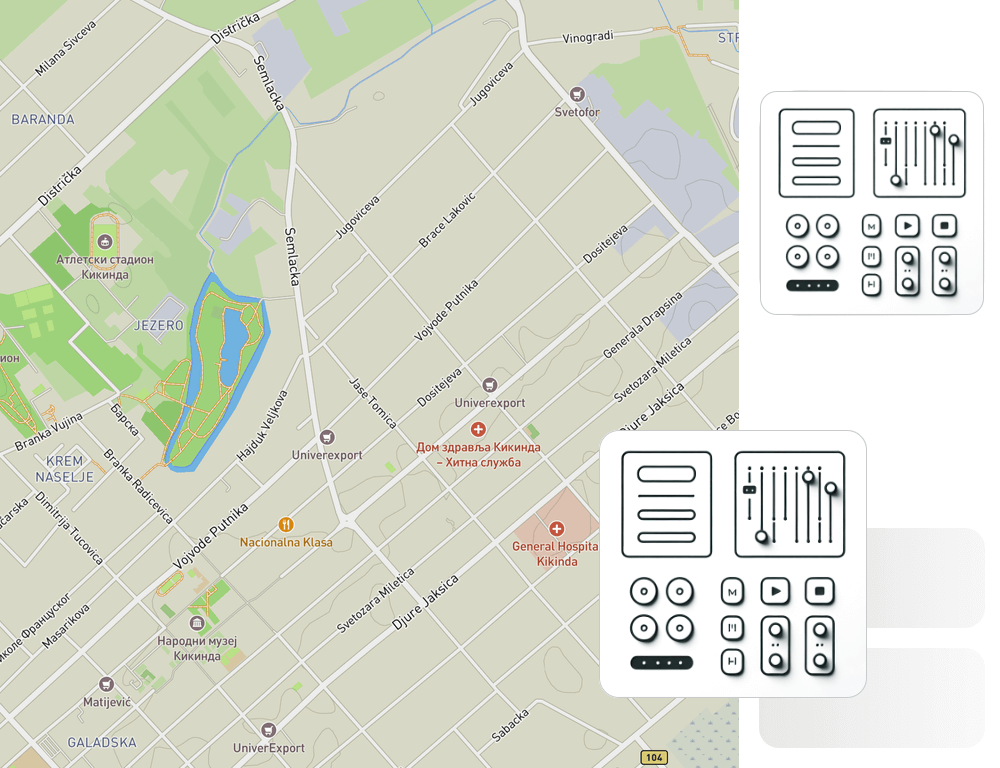

So, the essence of the problem with the test is that I have a map (as a canvas) from a third-party vendor (MapBox) and need to draw an object on it by making a certain number of clicks by Playwright. However, that element (a map) is actionable for Playwright from the moment it appears on the page, but the actual actionable state of the element is indefinable by its locator.

Fig. 1 and 2. Both states of the map are actionable for Playwright, but only the last one is truly interactable, and even then, only after some time after rendering

HTML code of the map is the same during all states of loading and rendering of the element on a page:

1. Canvas element is attached and visible on the page (the element is actionable for Playwright), but nothing is rendered inside:

<canvas

class="map-canvas"

tabindex="0"

aria-label="Map"

role="region"

width="1470"

height="956"

style="width: 1470px; height: 956px; cursor: crosshair;"

></canvas>

2. Canvas element has rendered content but is not yet actionable for internal logic:

<canvas

class="map-canvas"

tabindex="0"

aria-label="Map"

role="region"

width="1470"

height="956"

style="width: 1470px; height: 956px; cursor: crosshair;"

></canvas>

3. Canvas element is ready for action:

<canvas

class="map-canvas"

tabindex="0"

aria-label="Map"

role="region"

width="1470"

height="956"

style="width: 1470px; height: 956px; cursor: crosshair;"

></canvas>

The problem was compounded by the fact that it was hardly reproducible locally, manifested mainly in CI, and depended on CI runners’ performance and network bandwidth.

Studying documentation and StackOverflow on similar subjects did not get results. One-two discussions were mainly related to waiting for MapBox map’s data on the React app’s level.

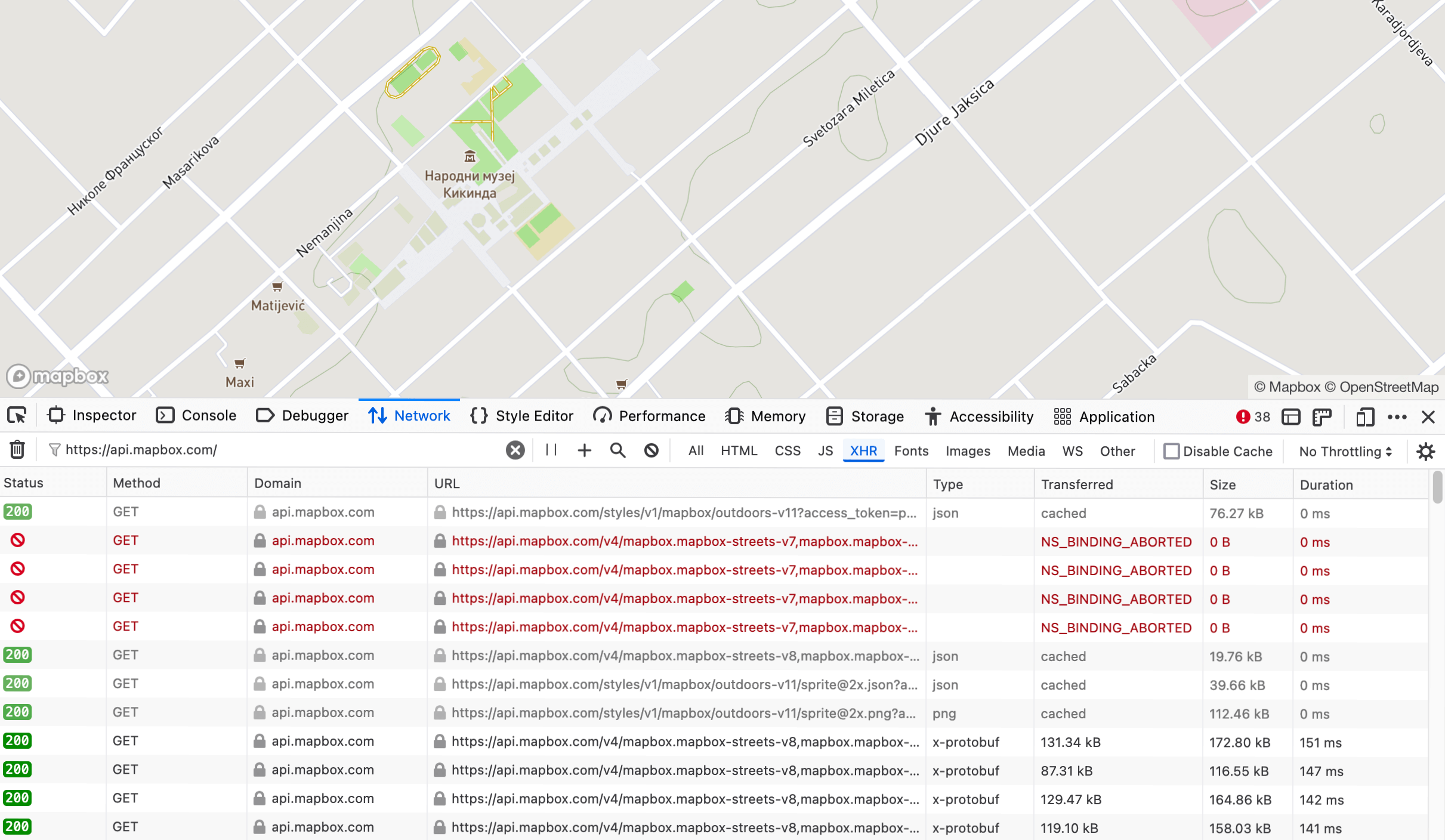

The key thing turned out to be the observation that rendering finishes once all MapBox’s elements are loaded (JSONs, styles, tiles, fonts, etc., which are needed for a custom map). And the canvas element becomes interactable, too, with almost no delay.

Fig. 3. Example of loading resource for the map from MapBox API

Thus, instead of adding an unconditional timeout before action, we can wait for a complete loading of desirable resources required for this action.

Playwright allows to perform various checks inside network activity through waitForResponse method.

To overcome flaks in all tests involving a map, I made a common function:

import { Page, expect } from "@playwright/test";

const mapBoxResouces = [

"https://api.mapbox.com/styles/v1/",

"https://api.mapbox.com/v4/mapbox.mapbox-streets-v8/",

// Required for a custom map

// "https://api.mapbox.com/fonts/v1/",

];

export async function openPageWithMapAwaiting(page: Page, path: string) {

await page.goto(path);

for (const resource of mapBoxResouces) {

const response = await page.waitForResponse(resp => resp.url().includes(resource));

await expect(response.status(), `Should response 200 for ${resource}`).toBe(200);

}

}

And call it in all required places inside the test steps:

test("Should have POIs on the map", async ({ page }) => {

await test.step("Open the home page", async () => openPageWithMapAwaiting(page, "/home"));

…

});

The described solution helped to negate the flakiness of the considered case.

It is worth clarifying that such a fix can be extended only to a small part of similar scenarios because it all depends on the context, test-cases, and business logic.

Connected articles:

- Timeouts Against Flaky Tests: True Cases with Playwright;

- One Technique for Fixing/Preventing Flaky Tests.

Read further on how to deal with flaky tests:

- The Ultimate Guide to Flaky Tests;

- Flaky tests: How to manage them practically;

- Fixing flaky tests;

- Reducing flaky builds by 18x;

- Flaky Tests at Google and How We Mitigate Them.

References:

- A. Romano, Z. Song, S. Grandhi, W. Yang, and W. Wang, “An Empirical Analysis of UI-based Flaky Tests,” in Proceedings of the 43rd International Conference on Software Engineering, 2021. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2103.02669

- Q. Luo, F. Hariri, L. Eloussi, and D. Marinov, “An empirical analysis of flaky tests,” in Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGSOFT International Symposium on Foundations of Software Engineering, 2014. https://doi.org/10.1145/2635868.2635920

- W. Lam, K. Muslu, H. Sajnani, and S. Thummalapenta, “A study on the lifecycle of flaky tests,” in Proceedings of the ACM/IEEE 42nd International Conference on Software Engineering, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1145/3377811.3381749

Copy @ Medium