Mitigate JavaScript Flaky Unit Tests

Flaky tests are the constant accompanying problem of autotests. However, unlike UI end-to-end browser tests, unit tests are less exposed to flakiness, but the issue still exists.

The approaches to mitigating flaky tests for E2E and unit tests are quite different.

The main differences between these tests lie in their very definition:

- A unit test is a type of software test that verifies the functionality of a specific, isolated piece of code — typically a function or method — by checking its output against expected results.

- An end-to-end (E2E) test is a type of software test that verifies the complete workflow of an application, from start to finish, to ensure all (or most of them) components — frontend, backend, database, and third-party services — function correctly together.

Next, I will consider ways to reduce the flakiness of unit tests on JavaScript, which has nothing in common with integration testing or complicated API and E2E tests that require execution of HTTP requests and browsers to run.

1. Rewrite your flaky tests

The most dominant reason of flaky tests is concurrency-related issues (e.g., async wait, race conditions, atomicity violations, or deadlocks) [1], [2]. And — this may sound silly and obvious — but rewriting tests is the most common and effective solution to eliminate the problem of these kinds of flaky tests [2], [3].

The following points outline the approaches to be followed when rewriting unit tests.

2. Maintain maximum test independence

Unit tests will be robust and reliable if they are self-contained and do not depend on the execution or results of other tests. Test independence is achieved by maintaining several aspects:

- Avoid sharing state across tests;

- Keep test data isolated;

- Avoid order-dependent tests.

For the code example below, I will use Vitest as a testing framework — it is not the most widely used in JavaScript (it is Jest now), but it is one of the fastest-growing ones [4].

Avoid sharing state across tests

The «state» may refer to variables or in-memory objects that can be accessed simultaneously by different tests. The easiest way to avoid this is to avoid having global variables in tests.

❌ Bad example

import { test, expect } from "vitest";

let counter = 0;

test("should increment counter", () => {

counter += 1;

expect(counter).toBe(1);

});

test("should decrement counter", () => {

counter -= 1;

expect(counter).toBe(0); // ❌ Fails if tests run in a different order due to shared variable

});

✅ Good example

import { test, expect } from "vitest";

test("should increment counter", () => {

let counter = 0;

counter += 1;

expect(counter).toBe(1);

});

test("should decrement counter", () => {

let counter = 0;

counter -= 1;

expect(counter).toBe(-1);

});

The example above keeps test variables inside each test function.

Keep test data isolated

As with the shared state, any resources, test files, and common variables/constants imported into tests should not be simultaneously accessed by different tests. Each test should create the test data entity only for itself, and it should not be reusable for other tests.

If test data is created for a test, it should be cleaned up after the test ends. Otherwise, if the test does not perform proper cleanup, it may fail when run more than once on the same machine [1].

If common variables/constants are imported as test data into the test file, it should be copied for each test. For objects, this can be done by deep cloning to prevent modifications of an original object.

import { test, expect } from "vitest";

import _ from "lodash";

const original = {

player: { name: "Messi", bib: 10 },

};

test("should not mutate the original object", () => {

const originalCopy = _.cloneDeep(original);

originalCopy.player.bib = 30;

expect(original.player.bib).toBe(10);

});

In the example above, a copy of the data is created in the test using _.cloneDeep() method, and subsequent operations are performed under the copied data while the original data stays untouched.

Avoid order-dependent tests

There are two types of order-dependency tests:

- First, «victims» pass when run in isolation but fail when run after another test(s), known as «polluter(s)» [5]. A polluter «pollutes/spoils» the state shared between the two tests (the first test in the bad example of «Avoid sharing state across tests» paragraph may be considered as a polluter).

- Second, «brittle» tests that fail when run in isolation but pass when run after another test(s) called a «state-setter(s)» [5]. The state-setters set up the initial state required for the brittle to pass.

Both types of described tests are legitimate to be present in API or E2E test sets due to the inherent complexity of the necessary order of HTTP requests or sequences of clicks in a browser. However, order dependency in unit tests is unacceptable — the necessary manipulations to bring the state to the desired condition should be carried out through the test fixtures or setup hooks, not through other tests or test steps.

3. Use hooks for preconditions and postconditions

The best way to bring the state of the testing function to the desired condition is by using beforeEach and/or beforeAll hooks (and afterEach or afterAll to teardown changes). These hooks will allow to keep order independency between tests.

❌ Bad example

import { expect, test } from 'vitest';

let dataBase: Record<string, string>[] = [];

test('should initialize data', () => {

dataBase.push({ player: 'Messi' });

expect(dataBase.length).toBe(1);

});

test('should get data', () => {

expect(dataBase[0].player).toBe('Messi'); // ❌ Fails if run in isolation or in random order

});

✅ Good example

import { beforeAll, expect, test } from 'vitest';

let dataBase: Record<string, string>[] = [];

beforeAll(() => {

dataBase.push({ player: 'Messi' });

});

test('should get data', () => {

expect(dataBase[0].player).toBe('Messi');

});

The example above works in any order or when run individually because it does not rely on another test to set up the state.

4. Be careful with the precision of checks

If you check one value against another, be tolerant of «inaccurate» checks and rounding checking values. Too precise values may cause flakiness, especially geographical coordinates and time.

❌ Bad example

import { test, expect } from "vitest";

import { calculateDistanceFunction } from "./calculate-distance-function";

test("should calculate distance", () => {

const result = calculateDistanceFunction(

[20.4489, 44.7866],

[19.8335, 45.2671],

);

expect(result).toBe(72.06735); // ❌ Too precise, may cause flakiness due to floating-point precision

});

✅ Good example

import { test, expect } from "vitest";

import { calculateDistanceFunction } from "./calculate-distance-function";

test("should calculate distance", () => {

const result = calculateDistanceFunction(

[20.4489, 44.7866],

[19.8335, 45.2671],

);

expect(result).toBeCloseTo(72, 0);

});

The example above uses a less strict comparison (check for km instead of cm precision) and toBeCloseTo as a more suitable assertion.

5. Brace yourself for time checks

Any autotest around time is potentially flaky. The problems lie in many areas: time zones, time accuracy (see «Be careful with the precision of checks» paragraph), test environment settings, time handling in the programming language itself (for example, JavaScript engines or test frameworks), computation speed, etc.

❌ Bad example

import { test, expect } from "vitest";

import { delayedFunction } from "./delayed-function";

test("should call callback after 100ms", async () => {

const start = Date.now();

await new Promise((resolve) => {

delayedFunction(() => {

const end = Date.now();

expect(end - start).toBe(100); // ❌ Too strict, while execution time may vary

resolve();

});

});

});

✅ Good example

import { test, expect } from "vitest";

import { delayedFunction } from "./delayed-function";

test("should call callback after approximately 100ms", async () => {

const start = Date.now();

await new Promise((resolve) => {

delayedFunction(() => {

const end = Date.now();

expect(end - start).toBeGreaterThanOrEqual(100);

expect(end - start).toBeLessThan(150);

resolve();

});

});

});

The example above allows a small margin for a calculated time check.

Unfortunately, in complex applications, you cannot do without time tests (simply because of business logic). It is enough to be aware that you have to be thoughtful when writing unit tests for functions based on time: use fake timers [6], use UTC instead of local time, and check seconds or milliseconds instead of microseconds.

Timeouts inside tests may also be classified as a potential problem with time. Timeouts and sleep calls are usually used to fix flaky tests, but they only decrease the chance of a flaky failure: running tests on different machines may make the sleep calls time out and trigger the flaky failures again [2].

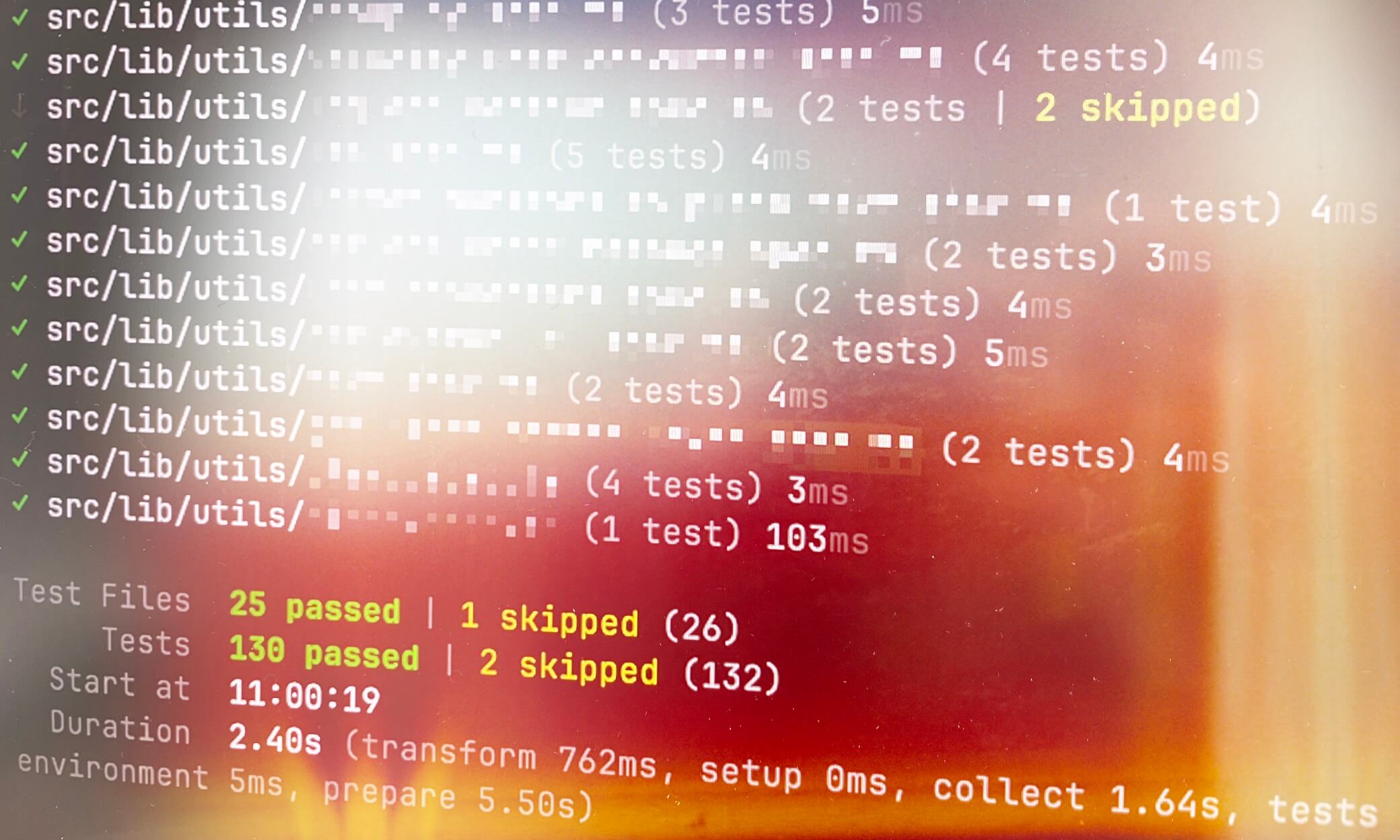

6. Test your tests

After the flaky test problem is solved, to make sure it does not reproduce on another test, it is a good practice to retest a fix on the whole test set.

To do this, you need to check the tests for order dependence by running them in random order or «shuffled».

Vitest allows shuffling on the test-file level: sequence.shuffle.files

npx vitest run --sequence.shuffle.files

And shuffling of tests inside each test-file: sequence.shuffle.tests

npx vitest run --sequence.shuffle.tests

Combination of these CLI options makes a test run completely random:

npx vitest run --sequence.shuffle.files --sequence.shuffle.tests

You can set your tests to always run in random order in CI. But in case of a failure, you may need to reproduce the order in which they were run, and this will not be so easy. So, to simplify debugging failed tests on a production scale, it may be better to run tests in CI in a predictable order.

Fully independent tests will allow them to be safely run in parallel, which will increase the speed of testing.

This article does not cover mocks (although fake timers are classified as mocks). On the one hand, this is a whole topic that needs more in-depth discussion. On the other hand, most of the above principles related to test independence can also be applied to mocks, such as not keeping a global context for mocks, not sharing the same mocks between tests, creating and deleting mocks inside hooks, etc.

References:

- Negar Hashemi, Amjed Tahir, and Shawn Rasheed, “An Empirical Study of Flaky Tests in JavaScript,” in 38th IEEE International Conference on Software Maintenance and Evolution (ICSME), 2022. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2207.01047

- Qingzhou Luo, Farah Hariri, Lamyaa Eloussi, and Darko Marinov, “An empirical analysis of flaky tests,” in Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGSOFT International Symposium on Foundations of Software Engineering, 2014. https://doi.org/10.1145/2635868.2635920

- Wing Lam, Kıvanc Muslu, Hitesh Sajnani, and Suresh Thummalapenta, “A study on the lifecycle of flaky tests,” in Proceedings of the ACM/IEEE 42nd International Conference on Software Engineering, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1145/3377811.3381749

- State of JavaScript 2024: Testing

- Negar Hashemi, Amjed Tahir, Shawn Rasheed, August Shi, and Rachel Blagojevic, “Detecting and Evaluating Order-Dependent Flaky Tests in JavaScript,” in 18th IEEE International Conference on Software Testing, Verification and Validation (ICST), 2025. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2501.12680

- Testing Library: Using Fake Timers

Copy @ Medium