Dictionary of Flaky Tests

Sometimes, as a test engineer, a familiar topic may turn out to be much more complex.

Like any automated testing engineer, I had to debug and fix various flaky tests (Timeouts Against Flaky Tests: True Cases with Playwright, One Technique for Fixing/Preventing Flaky Tests, One More Technique to Avoid Timeouts as Fix of Flaky Tests, and Mitigate JavaScript Flaky Unit Tests). Besides that, I turned to academic literature on flaky tests to properly understand the problem I am working on. I was surprised to find that many common terms had slightly different definitions from article to article, and some papers used exclusively computer science concepts rarely seen in real production test engineering practice.

To compile the list below, I used my notes and highlights from reading the articles, as well as the NotebookML AI research tool, to gather more of the frequently related terms from the corpus of articles I had read.

The causes of flaky tests, their mitigation techniques and fixing strategies, detection and prediction methods are outside the scope of this article.

The following are the most common terms and concepts related to flaky tests in computer science papers:

- Flaky test

- All tests are flaky (ATAF)

- Confusion matrix

- Deterministic outcome/result

- Non-deterministic outcome/result

- Distributed tests

- Entropy

- Failure burst lengths

- False alarm/alert

- Fault-revealing test

- Fault-triggering failure

- Flakiness

- Hard flakiness

- Soft flakiness

- Flakiness scoring

- Flake reduction (FR)

- Loss in fault detection (LFD)

- Flaky build

- Flaky failure

- Flaky rate / flake rate / flakiness rate / flaky-test-failure rate

- Flaky test suite

- Flaky test vocabulary

- Flip / transition

- Flip rate / transition frequency

- Infrastructure flakiness

- Non-hermetic tests

- Order dependency (OD)

- Probabilistic flakiness score (PFS)

- Quarantine

- Rank of flakiness

- Resource-affected flaky test (RAFT)

- SUT (System Under Test)

- CUT (Code Under Test)

- Systemic flakiness

- Test smells

Flaky test

There are many definitions of flaky test [1], and they all share the same idea: it is a test that passes or fails when executed repeatedly on the same version of the code.

A formal definition is as follows [2, 3, 4]: flaky test is a test that produces a non-deterministic outcome.

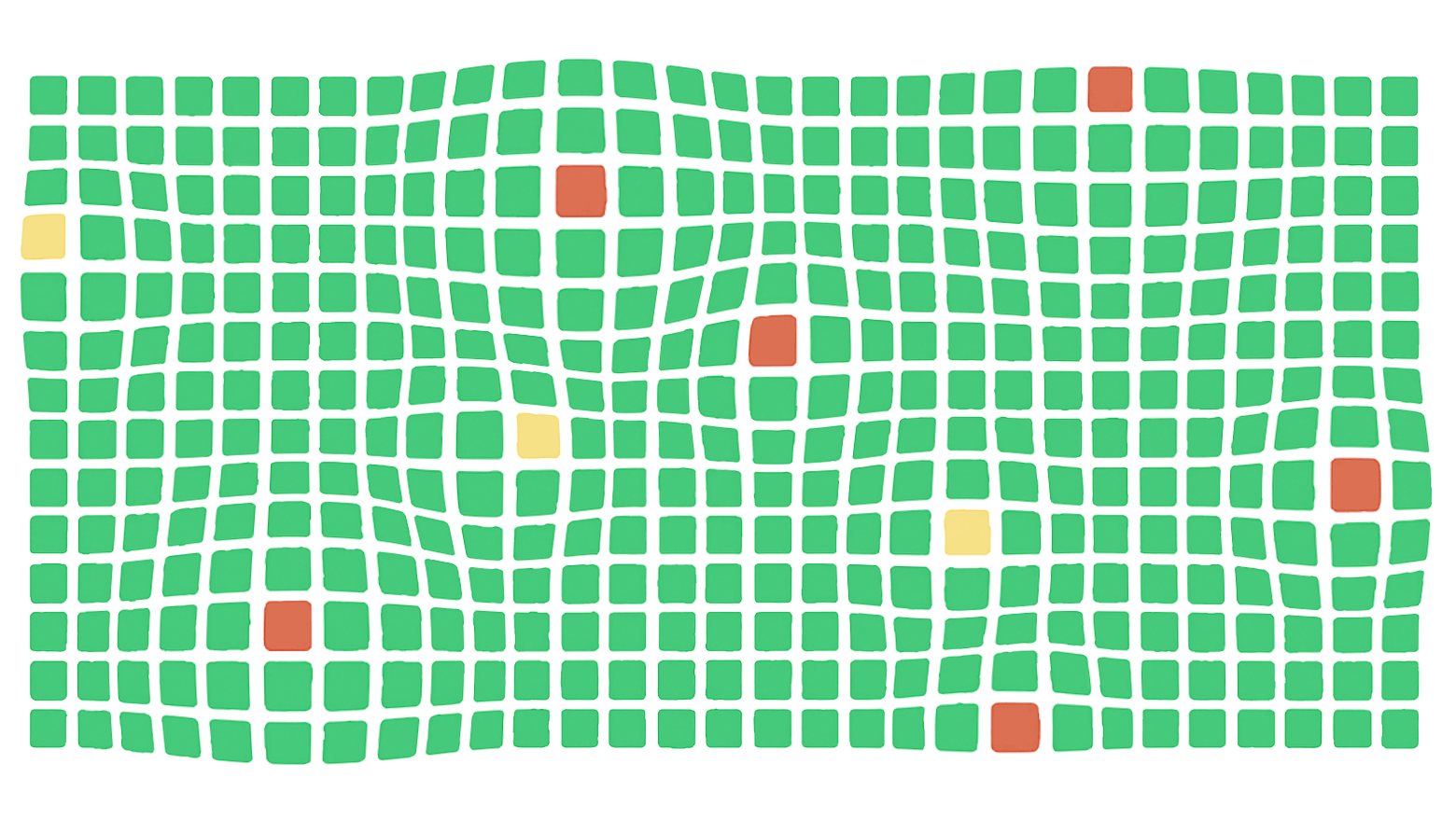

All tests are flaky (ATAF)

It is an assumption that all tests can be considered flaky [5]. The only difference between tests is how frequently they fail (it’s just sometimes this frequency can be zero).

Confusion matrix

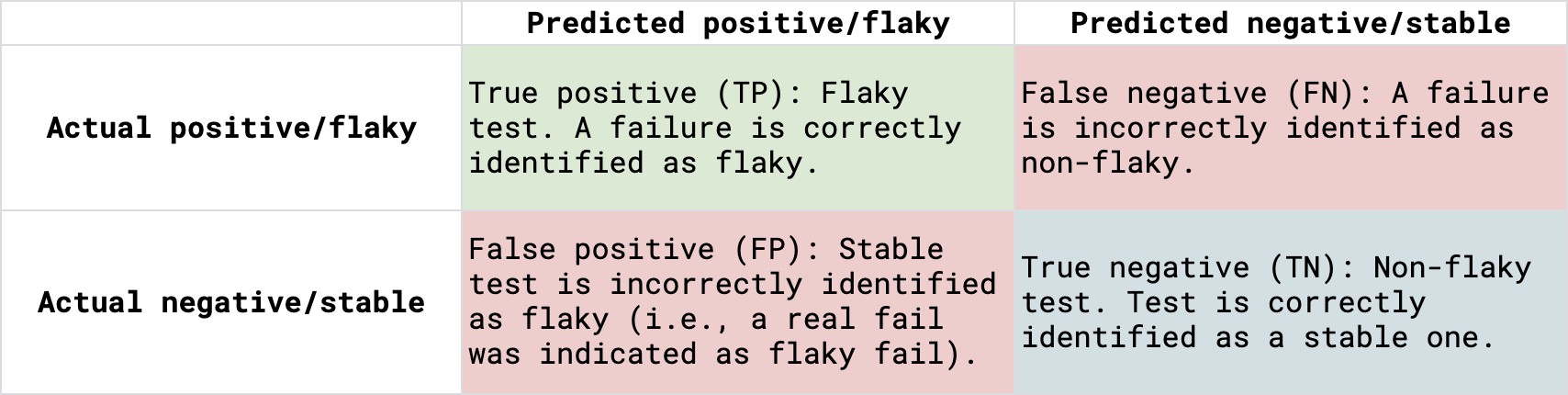

A confusion matrix is a method for classifying algorithm results. It is applicable in flaky test detection, prediction, classification, and evaluation [6, 7, 8, 9, 10].

The four components of the confusion matrix are defined in the context of classifying a test (or a failure) as «flaky» (the positive class) or «non-flaky» (the negative class):

- True Positive (TP): Flaky failure is correctly identified as flaky.

- False Negative (FN): Flaky failure is incorrectly identified as non-flaky (or matching true failures).

- False Positive (FP): Stable test is incorrectly classified as flaky.

- True Negative (TN): Stable (non-flaky) test results are correctly identified as stable; a true failure that does not match any flaky failure.

Fig. 1. Confusion matrix for flaky tests.

Practitioners may call FN and FP tests as «suspicious» because debugging the cause of failures takes a significant amount of time [36].

Deterministic outcome/result

This is an outcome that can be predicted exactly with 100% certainty from a given set of inputs and starting conditions. This implies that no randomness or uncertainty is involved.

Stable/reliable tests have deterministic results.

Non-deterministic outcome/result

This is an outcome that can vary even when the same inputs or conditions are repeated. This means the result cannot be predicted with certainty and may differ with each execution (i.e., inconsistent result).

A test is non-deterministic when it passes sometimes and fails sometimes [11].

Distributed tests

Tests whose execution involves multiple machines, environments, or SUTs simultaneously. Some papers [12] have questioned the impact on flakiness of running tests in distributed environments, but no correlations were found.

For example, running tests in parallel on different machines is distributed testing; running tests against a SUT deployed across multiple nodes is also distributed testing.

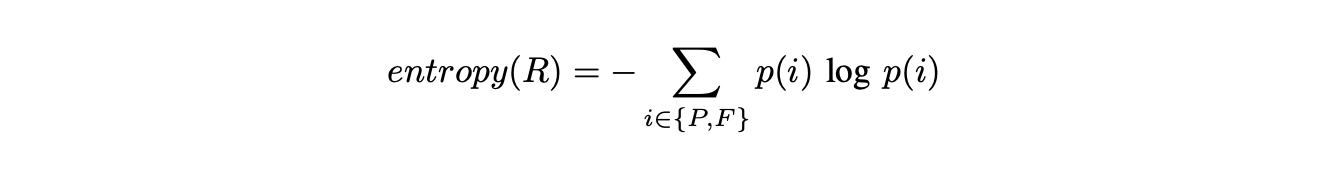

Entropy

As a scientific concept, it is a measure of randomness. In the context of flaky tests [1, 13, 14], it refers to a metric that detects flakiness based on the variability of test outcomes. Entropy measures the randomness (or uncertainty) in a test’s pass/fail history.

It is calculated using the formula:

Where:

- p(i) is the probability of each outcome i (pass or fail).

Unlike simple flip rate metrics, entropy focuses on the distribution ratio of passes to failures, ignoring the order in which these outcomes happen. This can help in identifying tests that unpredictably pass or fail, which is a hallmark of flaky tests.

Related terms: flip rate / transition frequency.

Failure burst lengths

This is the length of sequences of consecutive failures when repeatedly executing flaky tests, used to determine the necessary number of reruns to manifest flakiness [1, 15].

False alarm/alert

A test failure that results from a flaky test in the absence of a real defect or bug in the code under test [3, 8].

Fault-revealing test

A test that consistently failed after reruns in the same build, revealing a regression [8].

Fault-triggering failure

A failure caused by a fault-revealing test, where the test consistently fails after reruns [8], indicating a genuine regression.

Flakiness

Flakiness is the property of test outcomes being inconsistent, unreliable, or non-deterministic [16].

Hard flakiness

A definition of flakiness used in quantitative testing (e.g., A/B testing) that aligns with the traditional Boolean verdict definition; it is defined by a change in the definitive pass/fail verdict across re-executions [17].

Soft flakiness

A definition of flakiness specific to quantitative testing (e.g., A/B testing) that identifies flakiness based on variations in the quantitative fitness values across re-executions, even if the pass/fail verdict remains consistent [17].

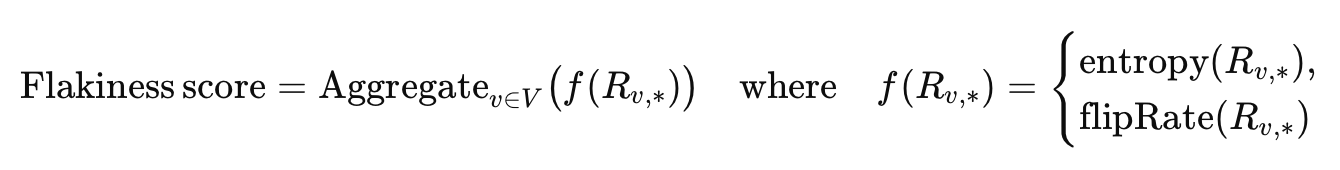

Flakiness scoring

It is the quantitative measurement of how unstable (or unreliable) a test is — how often its results (pass/fail) change under the same conditions. This measurement includes two key metrics: entropy and flip rate, which are aggregated over time to produce a flakiness score for each test.

The flakiness score shows how flakiness is distributed across tests [13] and can be used to monitor and detect changes in flakiness trends.

There is a similar internal metric in Meta: probabilistic flakiness score.

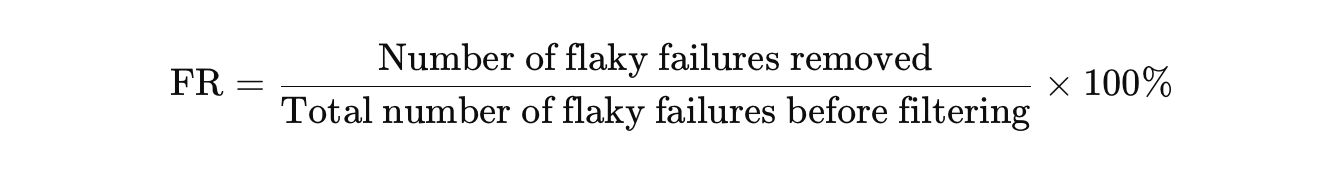

Flake reduction (FR)

It is a type of evaluation metric used to measure the effectiveness of flakiness scoring in filtering out flaky tests [13].

FR is defined as the percentage of flaky failures that are removed by filtering. It quantifies the amount of flaky noise eliminated after automatically ignoring tests whose flakiness scores exceed a seat threshold.

- High FR = good: The filtering removed most unreliable failures (less noise).

- Low FR = poor: Many flaky failures still remain.

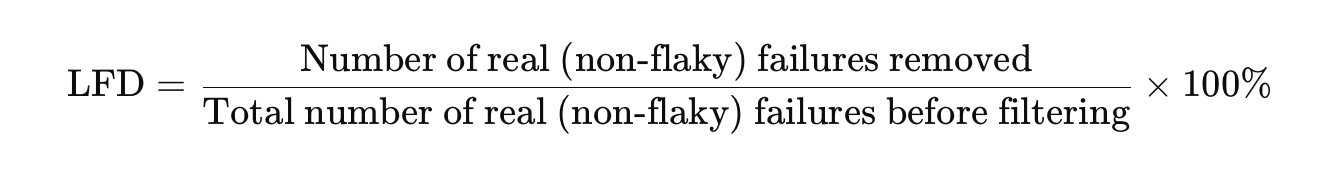

Loss in fault detection (LFD)

It is a type of evaluation metric used to measure the effectiveness of flakiness scoring in filtering out flaky tests [13].

LFD is the percentage of faults removed, where faults are defined as deterministic failures on a specific commit/version of SUT. It measures the undesired side effect of filtering out flaky tests; how many real faults (non-flaky faults) were filtered out by mistake.

- Low LFD = good: Few real bugs are accidentally ignored.

- High LFD = bad: Filtering removes real, deterministic failures.

Flaky build

It is a CI build that produces non-deterministic results (i.e., it randomly passes or fails). CI build may fail due to the result of a launched flaky test suite (which implies flakiness) or due to instability of the continuous integration system itself.

See infrastructure flakiness.

Flaky failure

A test failure that is specifically caused by a flaky test [8].

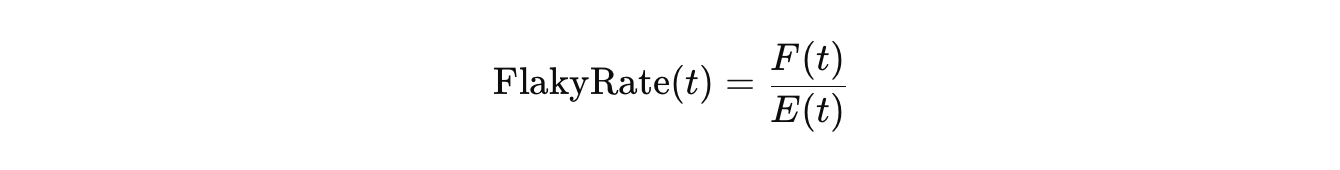

Flaky rate / flake rate / flakiness rate / flaky-test-failure rate

It quantifies how frequently a test exhibits flaky behavior [18]. Flaky rate measures the proportion of executions of a test that are flaky over a given observation period [8, 19].

Flaky rate is calculated using the formula:

Where:

- t — a specific test.

- F(t) — number of flaky executions of test t.

- E(t) — total number of executions of that test during the observed period. The number of test runs or builds is usually used here.

In other words, this rate shows a degree of flakiness.

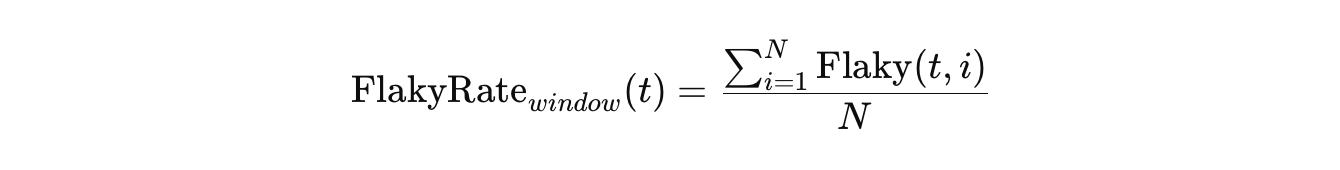

For calculating the flaky rate over a sliding time or build window, the formula becomes:

Where:

- t — a specific test.

- N — number of recent builds (the window size).

- Flaky(t,i) = 1 if test t was flaky in build i, otherwise 0.

Other ways to quantify flakiness include flip rate (measuring how often a test transitions between pass and fail) and entropy (measuring the randomness of results).

Flaky test suite

A test suite is considered flaky if it repeatedly passes or fails on the same version of the code. At the same time, a test suite is considered flaky if it contains flaky tests. Therefore, a flaky test suite is one that behaves non-deterministically due to the flaky tests it contains.

Flaky test vocabulary

It is a specific collection of source code identifiers, keywords, and linguistic patterns extracted from the test case source code that exhibit flakiness. This vocabulary is a key feature used in static analysis and machine learning models to predict test flakiness without needing to execute the tests [20, 21].

The vocabulary associated with flaky tests contains words such as job, table, action, wait, process, timeout, duration, thread, sleep, idle, etc., and may depend on the programming language [22] and test automation framework.

Flip / transition

A flip [13], or transition [8], means a change in the test result between runs, commits, or SUT versions.

- Pass → Fail: The test starts failing after a code change.

- Fail → Pass: The test starts passing again after a code change.

A transition (a flip in the test result) indicates a meaningful change in test behavior.

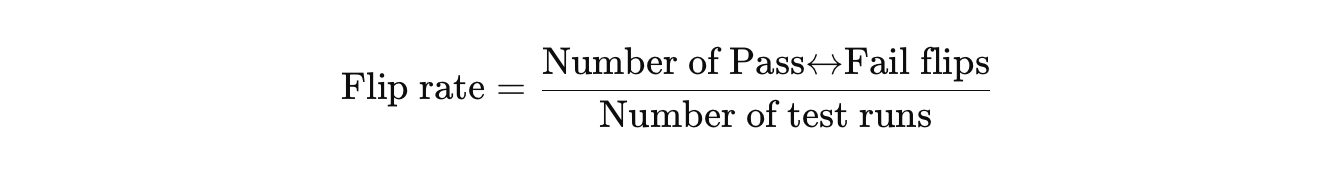

Flip rate / transition frequency

This term is found in articles about flakiness modeling [8, 13, 14]. The flip rate, or transition frequency, is a statistical measure of how often flips (transitions) happen [1]. It is the number of flips (transitions) of a test divided by the time window or the number of test runs.

It is calculated using the formula:

If the test never flips, its flip rate is 0. If the test flips once from Pass → Fail in 3 test runs, its flip rate is 1/3, or 0.33. If the test flips 3 times during 3 test runs, its flip rate is 3/3 = 1. So, the flip rate is able to capture the differences in the tests’ behavior.

Infrastructure flakiness

Such a test flakiness that arises from issues outside of the project code (i.e., CUT) but within the execution environment (e.g., non-determinism in the testing infrastructure, virtual machines (VM), Docker containers, CI/CD services, sandbox servers, simulators, downloading dependencies, etc.) [16].

Non-hermetic tests

Tests that are not purely isolated [13] from external dependencies and environment variables. These tests interact with real external systems, such as databases, file systems, networks, and other third-party services and deployed applications, while running. Because of these factors, non-hermetic tests are prone to flakiness, slower execution, and harder troubleshooting due to their reliance on external conditions.

Related terms: non-isolated tests, system tests, end-to-end tests, distributed tests.

Order dependency (OD)

Test order dependency refers to a situation in which the outcome of one test depends on the order in which tests are executed. OD is one of the main causes of flakiness [1, 23, 24, 25], and the reason why this term was put in the list is that it causes flakiness due to the tests themselves.

OD has its own dictionary of terms, including victim test, polluter, and state-setter, among others. However, these terms are outside the scope of this article and are discussed in corresponding articles [7, 26, 27].

See test smells because that is part of it.

Probabilistic flakiness score (PFS)

It is a statistical measure that quantifies how likely a given test is to fail due to flakiness, as opposed to a real regression in the code or a change in the system state.

PFS is a measurement of the probability of test flakiness and can be used to measure and monitor test reliability [28].

There is a similar internal metric in Apple: flakiness scoring.

Quarantine

The strategy of isolating known flaky tests from the main, «healthy» test suite into a dedicated area or list, typically to prevent them from blocking continuous integration and to allow later investigation and repair [29, 30].

Rank of flakiness

It is the severity (or prevalence) of flaky behavior (or instability) for a particular test.

There is no universal scale for it. Based on tests’ independent analysis of result histories and fault reports, some researchers [13] rank tests as not flaky (NF), slightly flaky (SF), flaky (F), or very flaky (VF).

Resource-affected flaky test (RAFT)

A test whose failure rate is statistically different when computational resources (like CPU cores or RAM) are constrained compared to an unconstrained test execution [31].

SUT (System Under Test)

Any piece of hardware or software that is currently being tested. SUT can be any type of application, API, UI, etc.

CUT (Code Under Test)

The programming code that the test case is intended to exercise. CUT can be a compiled program, library, function, method, etc.

CUT is a special case of SUT.

Systemic flakiness

The phenomenon where flaky tests exist in clusters and their failures co-occur during the same test suite runs, often sharing root causes like intermittent networking issues or instabilities in external dependencies [32].

Test smells

A test smell is a characteristic within test code that indicates a potential design problem or poor testing practice [33]. Test smells are symptoms of poor design choices in test coding [20] and represent deviations from the optimal way tests should be written, organized, and interact with each other [34].

According to some researchers [35], most flaky tests are causally related to test smells and can be fixed by applying refactoring operations.

References

- Owain Parry, Gregory M. Kapfhammer, Michael Hilton, and Phil McMinn. 2021. a Survey of Flaky Tests. ACM Transactions on Software Engineering and Methodology (TOSEM), Volume 31, Issue 1, Article No.: 17, Pages 1–74. https://doi.org/10.1145/3476105

- Qingzhou Luo, Farah Hariri, Lamyaa Eloussi, and Darko Marinov. 2014. An Empirical Analysis of Flaky Tests. Proceedings of the Symposium on the Foundations of Software Engineering (FSE). 643–653. https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/2635868.2635920 (Actually, this is the first empirical study centered on flakiness.)

- Moritz Eck, Fabio Palomba, Marco Castelluccio, and Alberto Bacchelli. 2019. Understanding Flaky Tests: The Developer’s Perspective. Proceedings of the 27th ACM Joint European Software Engineering Conference and Symposium on the Foundations of Software Engineering (ESEC/FSE ’19), August 26–30, 2019, Tallinn, Estonia. ACM, New York, NY, USA, 11 pages. https://doi.org/10.1145/3338906.3338945

- Azeem Ahmad, Ola Leifler, Kristian Sandahl. 2021. Empirical analysis of practitioners’ perceptions of test flakiness factors. Software Testing, Verification and Reliability, Volume 31, Issue 8. https://doi.org/10.1002/stvr.1791

- Mark Harman and Peter O’Hearn. 2018. From start-ups to scale-ups: Opportunities and open problems for static and dynamic program analysis. 2018 IEEE 18th International Working Conference on Source Code Analysis and Manipulation (SCAM). Madrid, Spain, 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1109/SCAM.2018.00009

- Abdulrahman Alshammari, Paul Ammann, Michael Hilton, and Jonathan Bell. 2024. 230,439 Test Failures Later: An Empirical Evaluation of Flaky Failure Classifiers. 2024 IEEE Conference on Software Testing, Verification and Validation (ICST). Toronto, ON, Canada. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2401.15788

- Owain Parry, Gregory M. Kapfhammer, Michael Hilton, and Phil McMinn. 2023. Empirically evaluating flaky test detection techniques combining test case rerunning and machine learning models. Empirical Software Engineering, Volume 28, article number 72, (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10664-023-10307-w

- Guillaume Haben, Sarra Habchi, Mike Papadakis, Maxime Cordy, and Yves Le Traon. 2023. The Importance of Discerning Flaky from Fault-triggering Test Failures: a Case Study on the Chromium CI. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2302.10594

- Roberto Verdecchia, Emilio Cruciani, Breno Miranda, and Antonia Bertolino. 2021. Know Your Neighbor: Fast Static Prediction of Test Flakiness. IEEE Access, Volume: 9. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2021.3082424

- Riddhi More and Jeremy S. Bradbury. 2025. An Analysis of LLM Fine-Tuning and Few-Shot Learning for Flaky Test Detection and Classification. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2502.02715

- Martin Fowler. 2021. Eradicating non-determinism in tests

- Alexander Berndt, Thomas Bach, and Sebastian Baltes. 2024. Do Test and Environmental Complexity Increase Flakiness? An Empirical Study of SAP HANA. ESEM ’24: Proceedings of the 18th ACM/IEEE International Symposium on Empirical Software Engineering and Measurement, Pages 572–581. https://doi.org/10.1145/3674805.369540

- Emily Kowalczyk, Karan Nair, Zebao Gao, Leo Silberstein, Teng Long, and Atif Memon. 2024. Modeling and ranking flaky tests at Apple. CSE-SEIP ’20: Proceedings of the ACM/IEEE 42nd International Conference on Software Engineering: Software Engineering in Practice, Pages 110–119. https://doi.org/10.1145/3377813.338137

- Martin Gruber, Michael Heine, Norbert Oster, Michael Philippsen, and Gordon Fraser. 2023. Practical Flaky Test Prediction using Common Code Evolution and Test History Data. Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Software Testing, Verification and Validation (ICST 2023). https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2302.09330

- Wing Lam, Stefan Winter, Angello Astorga, Victoria Stodden, and Darko Marinov. 2020. Understanding Reproducibility and Characteristics of Flaky Tests Through Test Reruns in Java Projects. 2020 IEEE 31st International Symposium on Software Reliability Engineering (ISSRE). https://doi.org/10.1109/ISSRE5003.2020.00045

- Amjed Tahir, Shawn Rasheed, Jens Dietrich, Negar Hashemi, and Lu Zhang. 2023. Test Flakiness’ Causes, Detection, Impact and Responses: A Multivocal Review. Journal of Systems and Software, Volume 206, December 2023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jss.2023.111837

- Mohammad Hossein Amini, Shervin Naseri, and Shiva Nejati. 2023. Evaluating the Impact of Flaky Simulators on Testing Autonomous Driving Systems. Empirical Software Engineering, Volume 29, article number 47, (2024). https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2311.18768

- Wing Lam, Kıvanç Muşlu, Hitesh Sajnani, and Suresh Thummalapenta. 2020. a Study on the Lifecycle of Flaky Tests. 42nd International Conference on Software Engineering (ICSE ’20), May 23–29, 2020, Seoul, Republic of Korea. ACM, New York, NY, USA, 12 pages. https://doi.org/10.1145/3377811.3381749

- Alexander Berndt, Thomas Bach, and Sebastian Baltes. 2024. Do Test and Environmental Complexity Increase Flakiness? An Empirical Study of SAP HANA. Proceedings of the 18th ACM / IEEE International Symposium on Empirical Software Engineering and Measurement (ESEM ’24), October 24–25, 2024, Barcelona, Spain. ACM, New York, NY, USA, 10 pages. https://doi.org/10.1145/3674805.3695407

- Gustavo Pinto, Breno Miranda, Supun Dissanayake, Marcelo d’Amorim, Christoph Treude, and Antonia Bertolino. 2020. What is the Vocabulary of Flaky Tests?. 17th International Conference on Mining Software Repositories (MSR ’20), October 5–6, 2020, Seoul, Republic of Korea. ACM, New York, NY, USA, 11 pages. https://doi.org/10.1145/3379597.3387482

- Guillaume Haben, Sarra Habchi, Mike Papadakis, Maxime Cordy, and Yves Le Traon. 2021. A Replication Study on the Usability of Code Vocabulary in Predicting Flaky Tests. 2021 IEEE/ACM 18th International Conference on Mining Software Repositories (MSR). https://doi.org/10.1109/MSR52588.2021.00034

- Azeem Ahmad, Xin Sun, Muhammad Rashid Naeem, Yasir Javed, Mohammad Akour, and Kristian Sandahl. 2025. Understanding Flaky Tests Through Linguistic Diversity: A Cross-Language and Comparative Machine Learning Study. IEEE Access, Volume: 13. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2025.3553626

- Owain Parry, Gregory M. Kapfhammer, Michael Hilton, and Phil McMinn. 2022. Surveying the Developer Experience of Flaky Tests. 44nd International Conference on Software Engineering: Software Engineering in Practice (ICSE-SEIP ’22), May 21–29, 2022, Pittsburgh, PA, USA. ACM, New York, NY, USA, 10 pages. https://doi.org/10.1145/3510457.3513037

- Wing Lam, Stefan Winter, Anjiang Wei, Tao Xie, Darko Marinov, and Jonathan Bell. 2022. A large-scale longitudinal study of flaky tests. Proceedings of the ACM on Programming Languages, Volume 4, Issue OOPSLA, Article No.: 202, Pages 1–29. https://doi.org/10.1145/3428270

- Alan Romano, Zihe Song, Sampath Grandhi, Wei Yang, and Weihang Wang. 2021. An Empirical Analysis of UI-based Flaky Tests. ICSE ’21: Proceedings of the 43rd International Conference on Software Engineering, Pages 1585–1597. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2103.02669

- Negar Hashemi, Amjed Tahir, Shawn Rasheed, August Shi, and Rachel Blagojevic. 2025. Detecting and Evaluating Order-Dependent Flaky Tests in JavaScript. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2501.12680

- Sai Zhang, Darioush Jalali, Jochen Wuttke, Kivanç Muşlu, Wing Lam, Michael D. Ernst, and David Notkin. 2014. Empirically revisiting the test independence assumption. ISSTA 2014: Proceedings of the 2014 International Symposium on Software Testing and Analysis, Pages 385–396. https://doi.org/10.1145/2610384.2610404

- Mateusz Machalica, Wojtek Chmiel, Stanislaw Swierc, and Ruslan Sakevych. 2020. Probabilistic flakiness: How do you test your tests?

- Negar Hashemi, Amjed Tahir, and Shawn Rasheed. 2022. An Empirical Study of Flaky Tests in JavaScript. 2022 IEEE International Conference on Software Maintenance and Evolution (ICSME). https://doi.org/10.1109/ICSME55016.2022.00011

- Fabian Leinen, Daniel Elsner, Alexander Pretschner, Andreas Stahlbauer, Michael Sailer, and Elmar Jürgens. 2024. Cost of Flaky Tests in Continuous Integration: An Industrial Case Study. 2024 IEEE Conference on Software Testing, Verification and Validation (ICST). https://doi.org/10.1109/ICST60714.2024.00037

- Denini Silva, Martin Gruber, Satyajit Gokhale, Ellen Arteca, Alexi Turcotte, Marcelo d’Amorim, Wing Lam, Stefan Winter, and Jonathan Bell. 2024. The Effects of Computational Resources on Flaky Tests. IEEE Transactions on Software Engineering, Volume 50, Issue 12, Pages 3104–3121. https://doi.org/10.1109/TSE.2024.3462251

- Owain Parry, Gregory Kapfhammer, Michael Hilton, and Phil McMinn. 2025. Systemic Flakiness: An Empirical Analysis of Co-Occurring Flaky Test Failures. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2504.16777

- Phil McMinn, Muhammad Firhard Roslan, and Gregory M. Kapfhammer. 2025. Beyond Test Flakiness: A Manifesto for a Holistic Approach to Test Suite Health. 2025 IEEE/ACM International Flaky Tests Workshop (FTW). https://doi.org/10.1109/FTW66604.2025.00007

- Bruno Camara, Marco Silva, Andre Endo, and Silvia Vergilio. 2025. On the use of test smells for prediction of flaky tests. SAST ’21: Proceedings of the 6th Brazilian Symposium on Systematic and Automated Software Testing, Pages 46–54. https://doi.org/10.1145/3482909.348291

- Fabio Palomba, and Andy Zaidman. 2017. Notice of Retraction: Does Refactoring of Test Smells Induce Fixing Flaky Tests?. 2017 IEEE International Conference on Software Maintenance and Evolution (ICSME). https://doi.org/10.1109/ICSME.2017.12

- Wing Lam, Patrice Godefroid, Suman Nath, Anirudh Santhiar, and Suresh Thummalapenta. 2019. Root Causing Flaky Tests in a Large-Scale Industrial Setting. Proceedings of the 28th ACM SIGSOFT International Symposium on Software Testing and Analysis (ISSTA ’19), July 15–19, 2019, Beijing, China. ACM, New York, NY, USA, 11 pages. https://doi.org/10.1145/3293882.3330570

Articles from the Google Testing Blog are often referenced, too:

- Mike Wacker. 2015. Just Say No to More End-to-End Tests

- John Micco. 2016. Flaky Tests at Google and How We Mitigate Them

- Jeff Listfield. 2017. Where do our flaky tests come from?

- George Pirocanac. 2020. Test Flakiness - One of the main challenges of automated testing

- George Pirocanac. 2021. Test Flakiness - One of the main challenges of automated testing (Part II)

Copy @ Medium